by Dirk Van Damme

Head of the Innovation and Measuring Division, Directorate for Education and Skills

More than hundred years ago, nations that are now members of the OECD introduced legislation to set the age compulsory education. Most countries obliged families to send their children to school from the age of 6 or 7. The gradual abolition of child labour and the need for a workforce with elementary skills – two consequences of the ‘second industrial revolution’ – convinced countries to impose compulsory education. Since then, education policy has focused on ensuring that all students are provided access to – and participate in – compulsory schooling. Many countries have also gradually increased the upper age limit of compulsory education. But for younger kids – under the age of 6 – families were seen as the most optimal environment for children’s care and upbringing.

But as more women entered the labour force and two-income families became the norm, the context in which children grew up changed dramatically. Working parents had to find a way to keep their children safe during their absence. But next to guaranteeing safety and physical care daytime crèches and child minders were not supposed to exert any pedagogical interference. Even when the realities of family life were changing, families – and mothers in particular – could keep up the belief that they and no one else were raising their offspring. Conservative romanticism about family life and ideals about motherhood – also shared by radical feminists – contributed to upholding the traditional pedagogical contract. When things didn’t work out well in practice, individual mothers were to be blamed, and many developed feelings of guilt and shame when professional and private roles came into conflict.

Things have started to change in the past few years. In many countries, not only has early childhood education expanded rapidly, but it has begun to evolve into different kinds of education targeted to distinct groups of children. The most recent Education Indicators in Focus brief, based on recent Education at a Glance and PISA data, documents the expansion of pre-primary education for children between the ages of three and six. This level of education – between childcare and early childhood development programmes for children under the age of 3 on the one hand, and primary education on the other – is now internationally recognised as a discrete step on the education ladder. In most OECD countries, well over 90% of 4-year-olds are enrolled, although participation among certain segments of the population remains low.

But is the expansion of pre-primary education changing the views on educating young kids? The recent research literature from the fields of developmental and cognitive psychology, neurosciences and economics is convincing on the benefits of early education – provided by specialised education programmes – for the cognitive, social and emotional development of children. Early childhood education is rapidly becoming a major area of policy attention, shared between education and social-welfare ministries. Apart from expanding provision policies now concentrate on raising the qualifications of staff and increasing the quality of the educational environments and pedagogical interventions at large. Early childhood education is no longer about offering children a safe and comfortable shelter while parents are out working, but about creating a pleasant, learning-rich environment from which young children can benefit. Some countries are now imposing pedagogical regulations on pre-primary education, much in the same way as they do for other levels of education, and for good reason. At the same time they also refrain from turning pre-primary education into a school-like environment. The pedagogy of stimulating kids to learn through play and joyful activity fortunately gains ground.

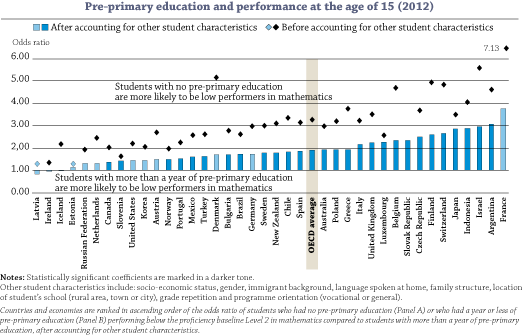

Evidence from PISA shows how beneficial early education can be. The chart above shows the relationship between students’ attendance at more than one year of pre-primary school and the mathematics performance of these students when they are 15 years old. Even after controlling for socio-economic status, gender, immigrant background, language spoken at home, family structure, location of student's school (rural area, town or city), grade repetition and programme orientation (vocational or general) students who had not attended any pre-primary education are almost twice as likely to be low performers in mathematics as students who had attended at least one year of pre-primary education.

The arguments and evidence in favour of early childhood education are now so powerful that they have flipped the traditional question of who should educate young children on its head: should governments stimulate families more to send their children to early childhood education? Families increasingly understand that high-quality early education programmes offer their children more than a safe place to spend a day; they can offer the kind of play and instruction that are the building blocks of healthy cognitive and social development. And governments come to realise that securing high-quality learning environments, with highly qualified staff, also require sound policies specifically tuned to the needs of these young kids.

Links:

What are the benefits from early childhood education? Education Indicators in Focus, issue No. 42, by Diogo Amaro de Paula

Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators

Chart source: OECD (2016a), Low-Performing Students: Why They Fall Behind and How to Help Them Succeed, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris,

Head of the Innovation and Measuring Division, Directorate for Education and Skills

More than hundred years ago, nations that are now members of the OECD introduced legislation to set the age compulsory education. Most countries obliged families to send their children to school from the age of 6 or 7. The gradual abolition of child labour and the need for a workforce with elementary skills – two consequences of the ‘second industrial revolution’ – convinced countries to impose compulsory education. Since then, education policy has focused on ensuring that all students are provided access to – and participate in – compulsory schooling. Many countries have also gradually increased the upper age limit of compulsory education. But for younger kids – under the age of 6 – families were seen as the most optimal environment for children’s care and upbringing.

But as more women entered the labour force and two-income families became the norm, the context in which children grew up changed dramatically. Working parents had to find a way to keep their children safe during their absence. But next to guaranteeing safety and physical care daytime crèches and child minders were not supposed to exert any pedagogical interference. Even when the realities of family life were changing, families – and mothers in particular – could keep up the belief that they and no one else were raising their offspring. Conservative romanticism about family life and ideals about motherhood – also shared by radical feminists – contributed to upholding the traditional pedagogical contract. When things didn’t work out well in practice, individual mothers were to be blamed, and many developed feelings of guilt and shame when professional and private roles came into conflict.

Things have started to change in the past few years. In many countries, not only has early childhood education expanded rapidly, but it has begun to evolve into different kinds of education targeted to distinct groups of children. The most recent Education Indicators in Focus brief, based on recent Education at a Glance and PISA data, documents the expansion of pre-primary education for children between the ages of three and six. This level of education – between childcare and early childhood development programmes for children under the age of 3 on the one hand, and primary education on the other – is now internationally recognised as a discrete step on the education ladder. In most OECD countries, well over 90% of 4-year-olds are enrolled, although participation among certain segments of the population remains low.

But is the expansion of pre-primary education changing the views on educating young kids? The recent research literature from the fields of developmental and cognitive psychology, neurosciences and economics is convincing on the benefits of early education – provided by specialised education programmes – for the cognitive, social and emotional development of children. Early childhood education is rapidly becoming a major area of policy attention, shared between education and social-welfare ministries. Apart from expanding provision policies now concentrate on raising the qualifications of staff and increasing the quality of the educational environments and pedagogical interventions at large. Early childhood education is no longer about offering children a safe and comfortable shelter while parents are out working, but about creating a pleasant, learning-rich environment from which young children can benefit. Some countries are now imposing pedagogical regulations on pre-primary education, much in the same way as they do for other levels of education, and for good reason. At the same time they also refrain from turning pre-primary education into a school-like environment. The pedagogy of stimulating kids to learn through play and joyful activity fortunately gains ground.

Evidence from PISA shows how beneficial early education can be. The chart above shows the relationship between students’ attendance at more than one year of pre-primary school and the mathematics performance of these students when they are 15 years old. Even after controlling for socio-economic status, gender, immigrant background, language spoken at home, family structure, location of student's school (rural area, town or city), grade repetition and programme orientation (vocational or general) students who had not attended any pre-primary education are almost twice as likely to be low performers in mathematics as students who had attended at least one year of pre-primary education.

The arguments and evidence in favour of early childhood education are now so powerful that they have flipped the traditional question of who should educate young children on its head: should governments stimulate families more to send their children to early childhood education? Families increasingly understand that high-quality early education programmes offer their children more than a safe place to spend a day; they can offer the kind of play and instruction that are the building blocks of healthy cognitive and social development. And governments come to realise that securing high-quality learning environments, with highly qualified staff, also require sound policies specifically tuned to the needs of these young kids.

Links:

What are the benefits from early childhood education? Education Indicators in Focus, issue No. 42, by Diogo Amaro de Paula

Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators

Chart source: OECD (2016a), Low-Performing Students: Why They Fall Behind and How to Help Them Succeed, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris,

0 comments:

Post a Comment